Dear Readers, I hope you’re doing well. This weekend’s post is a revision of an earlier piece. I reworked it (and improved it, I think :) Thank you for indulging me! If you enjoy it, please subscribe to my weekly posts.

Peace, Mel

Unbound Ties: An Adopted Heritage - Part Two, Returns to Mother.

Her magenta vase with a bold, swirling pattern clashes with the silk daffodils I bought from the gift shop, but Mom isn’t offended by the warring colors. Although her eyesight is limited by macular degeneration, she still sees bright yellow. And she’s pleased she paid just a quarter for the vase at the plant sale. To soften the clumsy, square table in her private room, I covered it with her old forest green embroidered tablecloth and set up framed photos of her mother, my dad, and my mom in the 1980s. The visual complexity of the space is further increased by a songbird that perches on the branch of a pink Japanese cherry tree painted on the base of Mom’s porcelain table lamp. The warm glow from its silk shade is a beacon toward which I maneuver her wheelchair, my cane across the armrests. When she is close enough to rest her arms on the table, I apply the wheelchair brakes and sit in the straight-back chair beside her.

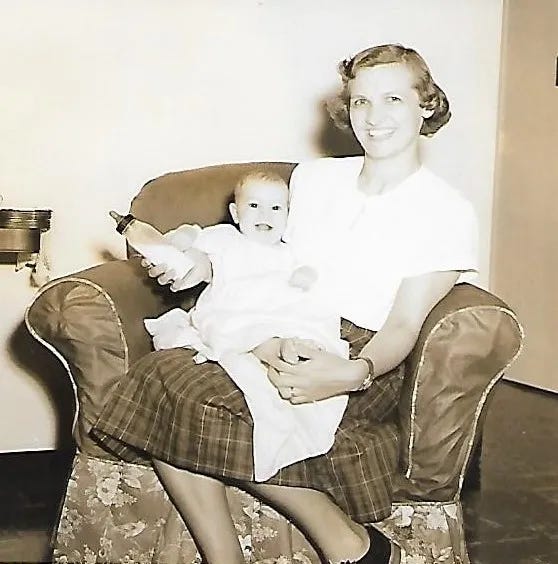

Bending forward in my seat, I open the lowest dresser drawer and retrieve a gilt cardboard box. Setting it down I lift the gold lid, my gesture is the cue to an activity we’ve repeated the past few years. I spread the contents, antique photos, on the table, and she selects a sepia image. Tilting it toward the light, she squints, and holds it closer to her face, struggling to discern the figures. The scenes of farm and city, friends and family are clear to me but have become dim to her. Her words are sentimental fragments of longing for her plain Pennsylvania homeplace. The memory of extended family is diminished. Her “Momma” is near, but her toil and hardship are washed away to an unreachable place of the heart, a peaceful place without want. I know a place like that in my bones, a longing for the home of my heart, and the kin I couldn’t have.

A formal family portrait was taken in a Mount Union studio — the Tokar brood of fourteen, ranked in rows and dressed for Sunday. Seated at the front between the youngest boys is Mrs. Anna Tokar, who died at sixty and Mom doesn’t remember. She points to her father, but strains to recognize the faces of her great-aunts and uncles. I was well-acquainted in childhood with at least six of these people from their visits to our New Jersey home, and my trips with my grandparents to New York City, Hoboken, Jersey City, and their Pennsylvania homes. But Mom’s memories of her biological family have further faded.

Mike Tokar was ten in 1909 when he sailed from Austria-Hungary with his two eldest sisters, Mary and Frances, entering through Ellis Island in New York City. They traveled west, probably by Pennsylvania Railroad from the new Penn Station to Huntingdon County in the Juniata River Valley of the Allegheny Mountains, to the Shirleysburg homestead where Mr. Tokar built a spacious log house with help from his neighbors, former Eastern European countrymen. They were dairy farmers in the old country and continued the trade on the fertile land. The land where colonial pioneers had farmed and defended against the British and fought and displaced native tribes throughout the Huntingdon Valley during the French and Indian Wars.

The East Broad Top Railroad ran from Mount Union to Orbisonia and into Robertsdale, the town of the coal mining company. In their teens, Mike met Julia Balas, whose parents were born in Poland. Mike drove his father’s milk route to Robertsdale, delivering to the Balas home. They were soon married, and Mike left the farm to work in the coal mine. When the mine closed in the Depression, he brought Julia and their two children to the Big City. With his interest in engine work, he quickly advanced in the mechanic’s trade, and in time, built a thriving tractor-trailer repair business, in his shop on Hudson Street: M&F Automotive, for “Mike and Family”.

Mom is sociable and lucid today, so we chat over a sepia print of her framed by Washington Square Park’s triumphal arch at age seven, her right hand is on her hip, and she wears a shirtwaist dress and Mary Janes. She peers under Buster Brown’s bangs at her mother’s box camera. A jointed plaster doll, dressed in a mustard-gold velour coat and a white fur-trimmed hat is a Christmas gift from her father’s employer, she tells me.

Emotions and stale sensations swirl through her room like the magenta pattern on her vase. At ninety-seven, she’s vulnerable, and aware I see she is. We struggle with time’s brevity. Despite my best intentions, my attempts to engage with my adoptive mother often fall short. She doesn’t reach out. She asks nothing of me. Perhaps, this is how she loves: wanting nothing in return. I want to repay her for caring for me, her ready wit, her humor, the sound of her high, warm laughter, and her needlework talent. Her strength, her kindness. But she has said she doesn’t understand me, stopping short of expressing regret for accepting responsibility for a child, not hers by birth. I couldn't be as close to her as she was to her mother. They were like sisters. I was the third wheel — or so I imagined. I was an adopted outsider.

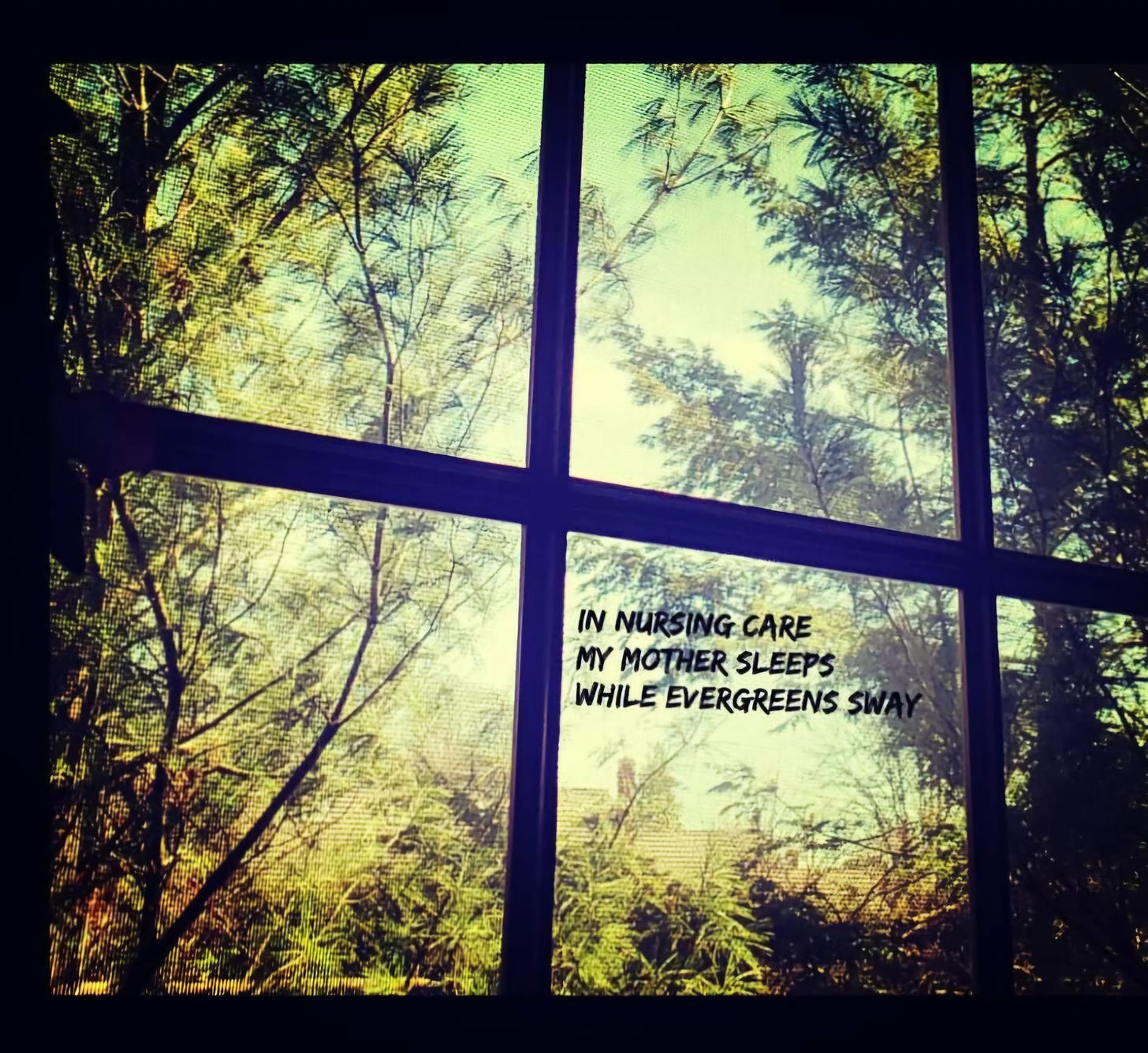

Mom dozes. I study her face, her occasional winces, and eye twitches. Restless, I rise with the cane I’ve used for right-sided weakness since my stroke at fifty-seven. I arrange her lotions, a tiny ceramic vase of dried flowers, and the chipped antique infant Jesus statue, whose two raised fingers snapped off long ago. Stormy pines sway outside the closed windows while she rests. I have risked intrusion in this solitary space that belongs to the very old.

When Mom needed more help in her old age, I supported her transition to assisted living. Yet, her faith in me is an unbound tie. A weak link. The nurse assures me she doesn’t mean the insensitive words, “You’re not my real daughter. I don’t want you here!” It's dementia talking. I no longer retort when she rages at me, unfiltered. I walk away. My unsolicited help exhausts me and reminds her that she relies on me. I walk a fine line bringing her necessities. A few luxuries. When it strikes her that she doesn't know who I am. Where I came from. That I was not the child she and the love of her life wanted but couldn’t have. That I couldn't replace that child. I’ve crossed the line. She is separating from me. Abandoned at birth, mother-loss is my original pain. I'm learning that love may find a form in loss.

Abandonment

My old mother says, “Don’t forget I'm here. Don't forget to call.”

My wound says, “Never stop loving me. Don’t leave. Take me with you.”

Thanks for sharing this nicely done bit of family history Mary ❤️

Beautifully written. You are fortunate to have had this experience to propel you on this creative journey