Dear Readers, I have a letter in prose poetry to share with you. Hope you enjoy it — and thank you so much for your subscriptions! ~ Mel

The Year I Knew You: A Letter to Leila Grace

Dear Leila,

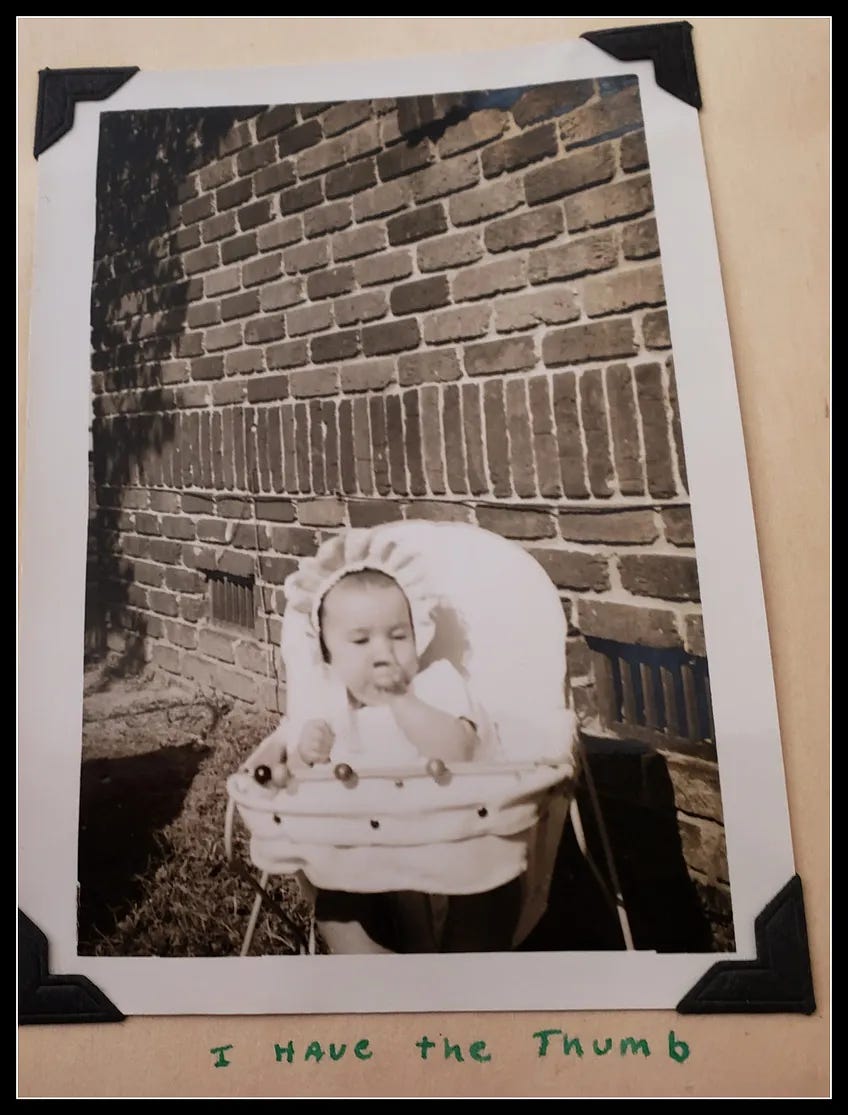

That year I learned your name, the summer I conjured and compared your face to mine, wanted to believe I once felt the high voice inflections in your gospel, your love songs, could hear the jukebox, the clink-and-clatter of bar bottles, the soldiers’ smoke I would have smelled but seeped in utero. When I quickened, or when in a dream I rested under your heart, I felt the hitch of your laughter and sobs and sucked my thumb — was it my left? I was late to break the habit, well past two. I needed you.

Leila, I recall our first phone call in late August 1993, “This is your daughter!” You expected my call — the day before, I connected with Karen, your daughter, my half-sister, after my long search. She confronted you with my claim that you were mine, too, and you denied me again and might have taken your secret to the grave. Only when she coaxed you, “Why would the woman call you from Pennsylvania if she didn’t have proof?” So you said, “Yes, it’s true,” and you admitted to giving birth to a girl in September 1951, when you were twenty-six and Karen was two. You said you simply “got up and left … I knew the nuns would take care of her.”

Karen told me you were fixated on TV shows that featured mother and child reunions but neither of you suspected a drama was about to unfold, that my search was bearing fruit. “How do you feel about my finding you?” Your coy response, in a soft Southern, “I think it’s great!” You must have meant it, Leila. But, I wonder, did you see me, hold me, touch me tentatively before the sisters swaddled me, and wheeled my bassinette to the hospital nursery, later, to their Saint Francis convent nursery? Catholic Charities persisted two months til they tracked you down, and got you to sign the release. You said you didn’t recall, didn’t remember, before you left me — walked out on me — the way, as Karen and I would much later learn, long after the reunion, that you’d done it again and again, walked out on an infant girl, your husband — her father — a few years later, and a newborn boy a year after Lottie was born.

This is what we now know: that you couldn’t bring yourself to tell the truth, the whole story, the story of your life, how you lived when I was conceived how your life when three half-siblings were conceived, and how lifestyle your style affected your choice — to abandon us all. A chanced upbringing and your lack of family support limited you, yes, but you chose to self-limit. I wasn’t to have the truth from you the truth of you and me, from you — mute, you were mute, beyond your proclamations of love, your honeymoon cards to Pennsylvania, the notes you wrote between my trips south, my visits during the year, I hoped hoped to learn from you, about the mother mother who couldn’t raise us. Instead, a blank slate something like the blank slate I was born with or as.

I was seventy-two when South Carolina law allowed my original birth certificate released to me, and for Catholic Charities to send me my file. It had taken twenty years to learn who my father was, the story of DNA that held the key to finding my father’s family. Now, I have my whole story. You named me after your aunt Ruth, and your sister, Ann, and so released me to the agency’s care, which saved me from the state orphanage, so the sisters could send me to their foundling home. I was Ruth Ann until my parents re-named me in adoption. But you knew nothing of that and didn’t ask what I had learned — that’s not your fault. At forty-one, I was at least as caught up in that year-long moment as you were, unsure how much more to ask or tell.

Karen met me at the airport with you, and I saw your moist, puffy eyes, your face flushed with an unknowable mixture of emotions: recollection? regret? guilt? shame? shock? A pang of pride? I‘m yours, your genes credit you — or was it woe, that I appeared to you, at all? I took charge of the feelings, wrapping my arms around your thickness with, “Hello, Momma, so good to see you!” When you yielded to my embrace, was your murmur meant for the gods? That you hadn’t dared to dream the infant, infants you left to charity would return to you one day? After your forty years of drowned sorrows, sadness, pleasure, and broken promises.

One husband stayed, the father of the child you kept, and you tried to raise her in a disarrayed home. Poor Suzie’s seizure disorder and the wild water were her demise at sixteen, and she went under in a tragic Texas creek. You and her father drank beer in the rented trailer and were not at the park, the picnic, or at the worst of accidents. You didn’t know it, but your children were all in danger of drowning. Your other four might have, too — there are other ways to drown — but for fortune or God’s grace we survived, but Leila Grace, you couldn’t save us, protect us.

You were all alone. Karen mercifully brought you home to South Carolina, you’d lived thirty-seven years in Texas. She looked after you. I feel sure you found peace, as ill as you were — we did, to a measure — all find peace. We buried you in October 1994 after our year-long reunion. By chance or all by fate. “They make it so hard to find our birth families,” I blurted out on that first phone call. “I don’t think that’s right.” With your reply, “No, not if you really want to find each other,” I’m content to believe one year was better than none.

Your daughter, Mary Ellen (Ruth Ann)

Thanks so much for reading. Please consider a free subscription. It means a lot to us indie authors!

Heartbreaking....someone once said that they teach us to drive, cook, etc, but leave out the most important thing in life....how to be a parent. I hope your meeting gave you a bit of happiness and peace.