Welcome to Roots and Branches and Memoir-ish Musings by Mel. Thanks so much for supporting my work.

Depth and Distance: A Lyric of Loss

Part 1.

At our first meeting in 1993, I learned from my maternal half-sister that our grandparents had isolated from the extended family, that Grandpa, although he had a good mind as a young man, didn't encourage his children's education, nor that of my sister — she lived in his household through childhood — that, by his abuse and lack of ambition, the mental and physical health of our mother and her siblings was not paramount to him. His father and brothers were successful farmers, but he chose to be a sharecropper and a sweeper in the cotton mill. Our mother was out of school by fourth grade, was a troubled teen, leaving home to work in the mill and bars, married and divorced quickly three times, had at least four infants, and gave away at least three. The child she kept died by drowning as a result of her neglect. We who have survived have had our trials.

Part 2.

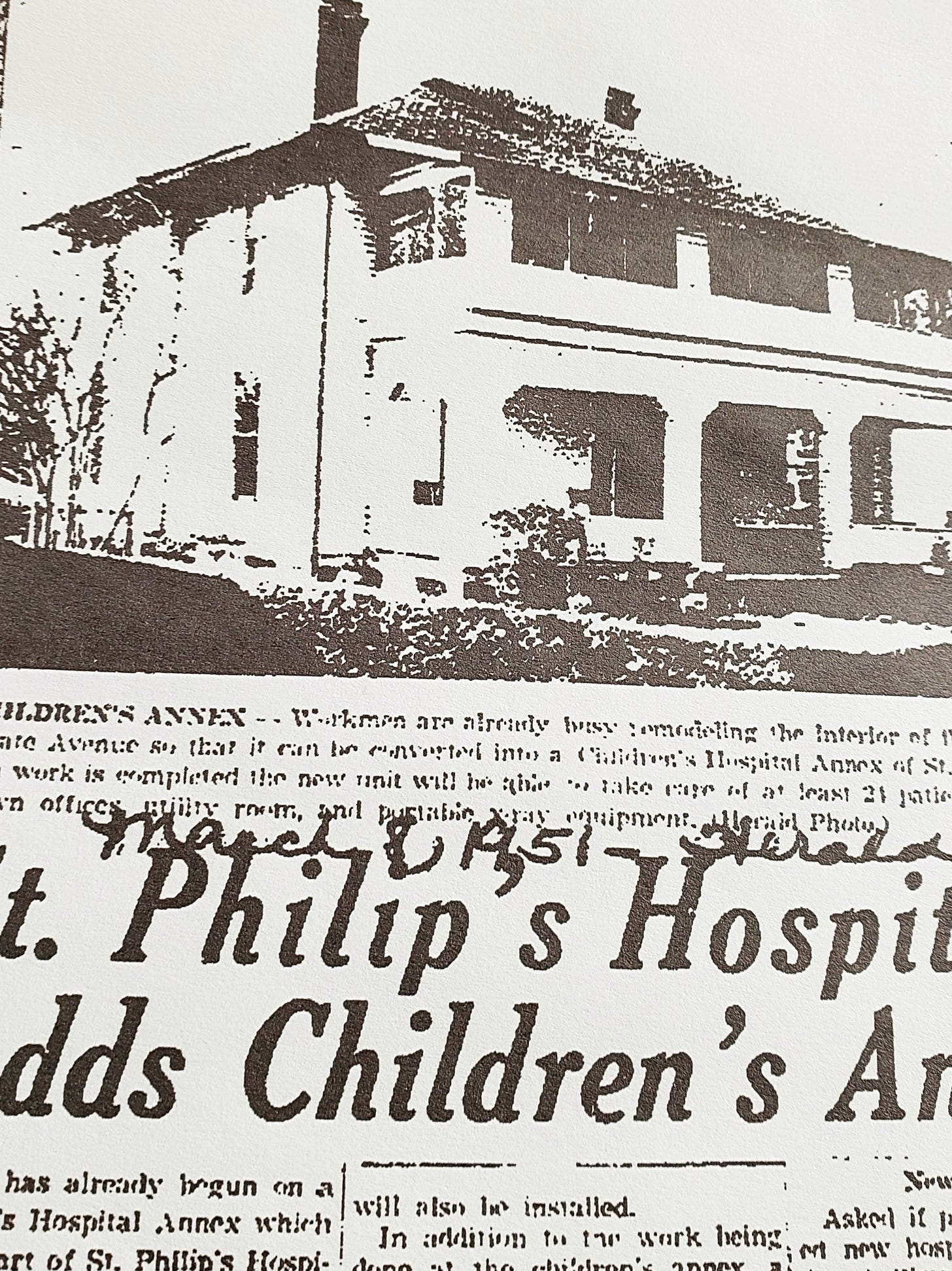

How to describe the effects of maternal severance and abandonment? Her parents’ unschooled, grinding life, and its effects on her mental and physical health, transferred to me. I have a sense of abeyance, neither here nor there without her, in the hospital foundling unit. She left me with the nuns and no family, in September 1951. Her mother didn't want me, she already had my sister to take care of in a fashion. When Catholic Charities located her two months later, she signed the release papers, and I was soon gone from Greenville, across the state to the Rock Hill infant home, where I waited with other relinquished infants who, like me, were admitted, waited, then discharged with the hope of a family's love.

In late February 1952, it was my turn, and the nervous and thrilled prospective adoptive Air Force couple brought me to their tiny apartment in Sumter, the first of two homes in South Carolina, and the first of seven in three states in my first three years as a military officer's daughter. It was the start of my post-war life with a committed and sincere couple who had deep compassion for a motherless infant, thankful for the gift of a child they couldn't have, and in whom they wanted desperately to see their reflection.

Ours was a kind of detached, unrequited, uncertain love: The child was adored until her differences, her native willfulness, and her neurotic sensitivity emerged, and could not be erased. Could not be fixed. For the new father, military duty was foremost, all but encompassing, the frequently lengthy absences, the new mother's loneliness and nerves, the abrupt moves, the whirl of school transfers, the confusion of goodbyes and readjustments, the discipline, the cold war anxiety, and the culture of secrecy — the dichotomy of privilege and gratitude, and the feral shame and guilt of what was unknown, but assumed. What could not be fixed was the profound loss and bewilderment of an adoptee's identity.

Part 3.

I was three and dressed for bed when he carried me to the front driveway and pointed toward the full moon and a punctuation of stars above the pin oak branches. I couldn’t bear such immediacy, the terror of tumbling into an unfathomable depth and distance, the black, empty surround of vastness. I twisted and contorted in protest, “No! Don’t show me!” I’d rather have fled from my daddy’s arms than face the desolation of the incomprehensible, unattributable, chaos of abandonment, the panic of primal severance. He would soon leave again, and again. He chided, called me a baby, as he carried me to my safe bed. The streetlight and moon shared space between the tilt of Venetian blinds as I drifted unafraid among the wallpaper flowers, chasing a repetition of dreams far above the pin oak branches. ✨️

I'm so glad you're getting settled into your new home. At the same time, sharing the chaos of childhood homes from birth with such eloquent and sensitive language.