Hello, kind readers ~ As promised, I have the 2nd part of the prose poem I shared last week. If you’d like to support my writing, (I hope you enjoy it!) please consider following me, or signing up for a free or paid subscription to my regular posts. Thanks so much for being here. Here is the link to the first The Lost Ones

A Journey Home ~ Part 2. Peace in Knowing

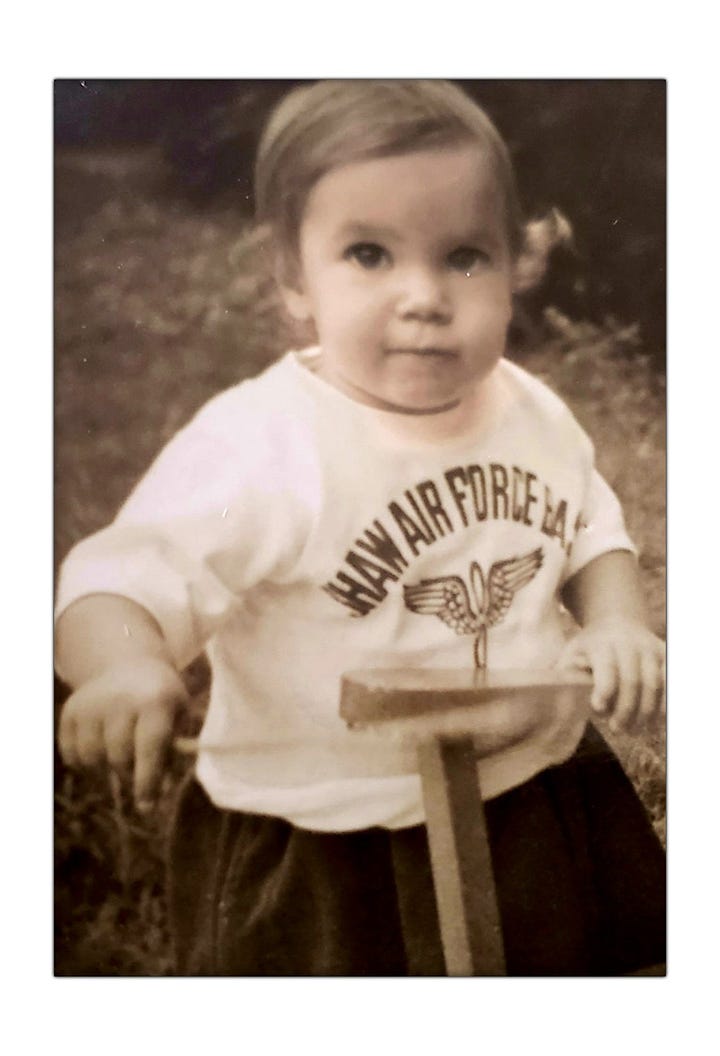

On a late spring afternoon in 1991 in our Bucks-Mont Pennsylvania townhouse, I pen a note on a yellow-lined pad. I roll a sheet of ecru bond onto the carriage of my indispensable portable Smith Corona Coronet. Typing tapping, tap tap tap to the South Carolina agencies that control the birth records of adoptees, who call the process fair. Inquiring. Seeking. She and I parted nearly anonymously in the Catholic hospital forty years earlier, that much I have learned. I am looking for my first mother. On the wide white Ikea desk, the white phone wire is curled, poised like a pale coiled snake set to strike, and I am resolved. With a Bic, a landline, and my native determination, I am ready. So much is unknown, isn’t here, missing information, some is faulty. I need leads. I had a sure lead, but it was misdirected, and I lost weeks.

Ann, an adoptee ally and local gumshoe historian, copied Greenville directory Lee pages. What happened, you may ask? Crucial data had come to me: my name at birth, Ruth Ann Lee, prompting my knee-jerk elation, joy, optimism, leading to frustration. I later learned my mother married Lee in Bilouxi, divorcing him when the baby was born in Greenville, in August 1948, two years before me — she kept his name but wasn’t ready to mother. The social services report noted Karn Lee was the two-year-old living with her mother’s parents. She couldn’t ask her parents to take another baby, the report said. I need must have her maiden name. Still, the agency holds it back. The misunderstood, misdirected, misguided meanderings cost time, money, and wasted emotion.

Pay another fee, and now, her full name. An adoptee advocate has given me her name, and the location of her parents’ home at the time of my birth: rural Greenville. It’s been a year since I learned my name at birth, and there was no more to tell me. No identifying information. Until a record breach for my mother’s maiden name. If only this vital information was given to me — an adult adoptee— on request, not kept from me under state seal. The infantilizing of adoptees.

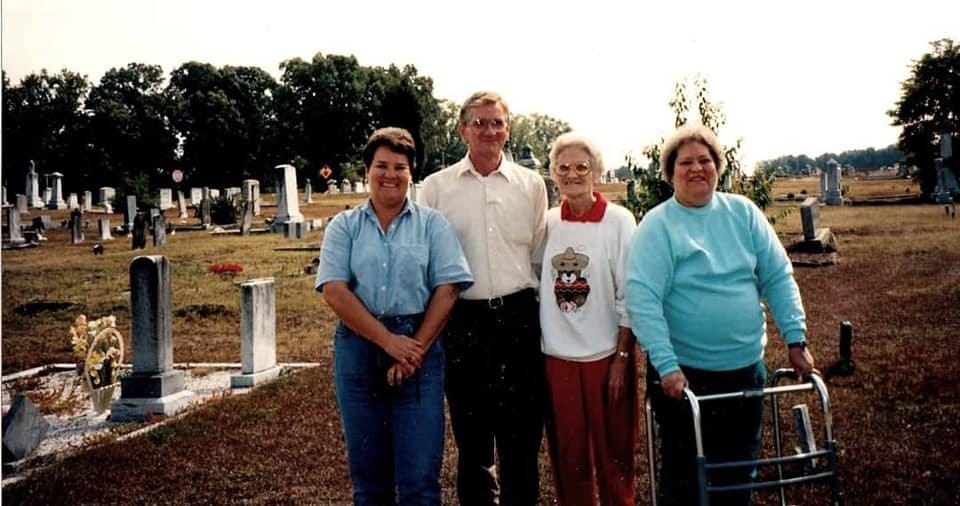

Leila Grace Cox, I ran with the vital information to a Greenville genealogist who had compiled a comprehensive cemetery survey. Ann told me she’d send me the report. She would send it. She sent it to me that summer of ‘92. Sent it in a manila envelope to me in Horsham, PA. I opened it at my kitchen table, opened it, unfolded the report. Fierce, I was, to find in the list of Greenville Cemeteries, Cox, and related Lenderman highlighted! The layout, the list of graves: Frank and Corrie Cox, my mother’s parents, their first-born newborn boy, Frank’s parents, John and Mary Lenderman Cox, their parents, sisters, brothers, aunts, uncles, and infants. All their markers and monuments were in the Churchyard of Antioch Christian Church. Heritage. My heritage. In the Churchyard of Antioch Christian Church.

In the envelope, their nearby land and farms, boundaries in line drawings, the lines of Fork Shoals of the Reedy River, and the Grove pioneer settlement. Tucked inside were the Greenville Cox phone directory pages for hours of cold-calling, rejections, denials, wrong numbers, and party unknowns, until a second cousin, warm and welcoming, Lawrence, happy to put me in touch, connect me with Karen and Leila. My heart was full!

Now Karen knew. Leila never said she had given birth to another daughter when Karen was two. Why had she held it close, never told? Karen called her Momma, so I did, too. Momma told me she was thrilled to be found. That I found her. Since Karen hadn’t left the place where she raised her three children, Leila knew how to reach her, though estranged for most of the thirty-seven years Leila lived in Texas. Karen hurried to her hospital bedside. She would return to bring her back home when she was stronger: Diabetes. Amputation. Dialysis. Widowed.

Karen said Leila had been immersed in afternoon T.V. mother-and-child reunions, viewing their moments of triumph, of ecstasy vicariously since she’d brought her home to South Carolina. “Now I know why,” she said. Wishing, but not believing, not trusting herself to be better. Not encouraged at home. Her lifetime of loss left her longing, having no resources, and no recourse. She couldn’t, or chose not to find a way out of the trap of her life. She was born into her father’s self-imposed hardships, that he inflicted on his family. He gave up chances, chances at something better, from his successful farming family, ministry school, abandoned for sharecropping and sweeping up in a textile mill. He caused his wife and children to struggle in confining surroundings. Made my mother leave school after fourth grade. Her younger sister needed guidance, as she was mentally challenged. One brother escaped to the military, then to insurance sales, and had a nice family, wanted to adopt Karen, but Leila was adamant. Another brother met a sorry end from an undetermined cause —asphyxia? In the State Hospital, 1951, where he was committed for criminal behavior. Epilepsy.

Leila hated her life, Karen said. Couldn’t settle down, married at sixteen to an older soldier, divorcing him while he was overseas. Then, another soldier, Karen’s birth, and that divorce. Then, again — and was that me? She wouldn’t say. When, at twenty-six, she gave me life, but no home, was it the easy way out? Was there no other way? Only to make mounds of trouble for herself, and us? To spite her family? Her lovers? Had she panicked, felt remorse? Escaped? Did she abandon me coldly, or had she thought it grace — her middle name — to the hands of the good sisters of Saint Francis? Leila, found by Catholic Charities two months later, urged to sign the release paper, or, as I now know, I would have to go into the State system. By chance, I was given a stable home and a chance.

When Karen was in elementary school, Momma took her to Texas by Greyhound, into her chaotic world, a debacle of trailer parks, transience, turmoil, and neglect. She wanted to raise her daughters together, with Susan’s father, an alcoholic. Leila brought Karen back to South Carolina by Greyhound when she saw it wasn’t working. She brought her to Mr. Lee who gave her a chance for a better life.

Susan, who had a seizure disorder, drowned at a picnic. The creek was raging. She was not the only fatality. Her father was summoned to the park to identify his sixteen-year-old daughter.

Lottie, Leila’s third daughter — so now we knew Susan was her fourth daughter — appeared on an internet chat board. Does anyone know Leila? She posted the query for her mother. Leila had died years earlier at the posting and was gone nearly thirty years when Karen and I saw Lottie’s post. We looked up Lottie, looked our half-sister up in the South Carolina town where Leila gave her life in 1954, left her with her father at six weeks. Leila never said, when we reunited, she could have said, when I found our mother. How could she not tell us so we could see Lottie, together, then? We are still in reunion — we are three half-sisters.

I threw myself into a DNA search for my father after we found Lottie. En route, I enlisted the help of a genetic genealogist who taught the technique, trained me, and showed me the Ancestry.com ropes. I meandered around and extended many lines, set up test trees, ruled out my two maternal half-sisters’ chromosomes, and sifted and sorted until I matched with a close cousin who ushered me to my father’s sister. And my four half-siblings — three sisters and a brother. Their father, my father, too, died in 1973. Sister, Teri, and brother, George died in 2023. My lost ones. I missed their kinship during my youth.

Do you believe, as I do, that my first mother’s illness, her return signaled me, and propelled me, prompted my search? Can it be propinquity — the sense of closeness of blood, of kin — if you haven’t learned their name? Did I sense her movement, sense she was near, a sense of elapsed time? Was it the strong pull of compassion, the urgent bond of birth that drew us three together? Together for one year. Together.

During that year, the year before she died, I visited, and we exchanged cards and calls. She told me I had stayed in her heart when she left me, as an infant. She had named me Ruth Ann, and I was Ruth Ann until I was adopted. I couldn’t picture her, but she had stayed in my heart, my psyche. We both had phantoms, the lost, repressed, suppressed kin. I traveled in my heart, followed our ancestor’s pioneer route, our Scots-Irish, our German forebears from Pennsylvania down the Blue Ridge to the home in my heart. She and I found peace in knowing.

Thank you for your comments.

beautiful Mel,again you bring me to tears